Anyone who knows anything about me knows I am a massive Harry Potter fan. I caught those books and movies pretty much at the same time during my childhood and both forms of media completely captured my interest and formed the foundation of the love I still have for the Wizarding World.

Having read the books midway through the release of the films, I didn’t find myself comparing one to the other, instead seeing them as different iterations of the same story, both with things I preferred over the other depending on the medium I felt like consuming Harry’s story through that day.

Now, looking back on the movie adaptations of the books, I find that the birth and success of the series on the big screen is something of a miracle in terms of epic young-adult fantasy. Ever since the release of both The Philosopher’s Stone and The Fellowship of the Ring in 2001, studios everywhere have been trying to recapture the potential of fantasy stories, with only a few stories of success.

For Harry Potter in particular, I find it interesting that the movies managed to handle the success of the books, it being a fantasy series more directed for children, and the track record of failed fantasy adaptations to the big screen, and somehow deliver a product that millions found enjoyable and remained loyal to for ten years of film making.

While the movies are not perfect by any means, the journey of this project holds many lessons in movie making for any fan of the art form and for the young children like myself that the movies were targeted towards, it serves as great introduction into what movies can inspire in their viewers when there is true competency, skill and resourcefulness behind the camera.

Perhaps the most relevant factor of cinematic choices throughout the Harry Potter series is the fact that the movies experienced the influence of four different directors from beginning to end. All four brought a different flavor to the movies they directed, with very different styles and approaches to the story, characters, structure and ambience of this world and it is interesting to look at each of them and examine the choices they made, what worked and what didn’t and what can be learned by every viewer through the experience of watching this series.

Chris Columbus – Building the World

The first director, Chris Columbus, was at the helm of the first two movies, Philosopher’s Stone (PS) and Chamber of Secrets (CS). These movies are characterized by a focus on the whimsy and charm of this world that the story takes place in. The colors are vibrant and strong, the amazing score by John Williams is mystical and exciting, and the whole experience feels like a fun, engaging and mysterious adventure for the whole family. Columbus made the smart decision of prioritizing characterization and world-building over plot and themes. The audience needed to fall in love with this setting and these characters before being asked to dive deep into the story and what’s behind it.

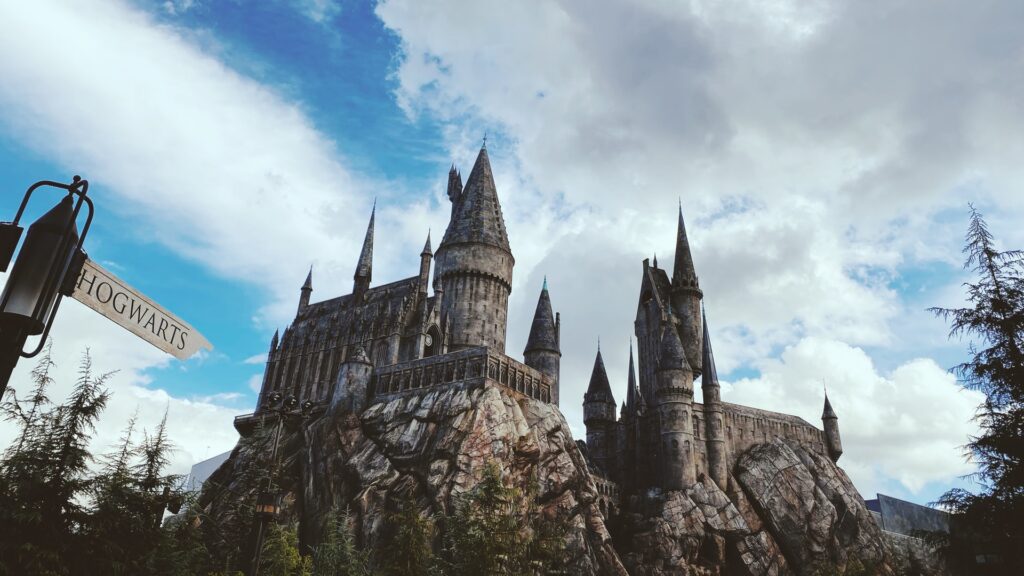

The focus on creating an enticing and iconic world is evident best through the work of the series’ production designer, Stuart Craig. Easily the most consistently amazing aspect of the Harry Potter movies is the production design, and this stellar production is noticed best in the first movies when we are introduced to these locations for the first time. Hogwarts, Diagon-Alley, Number Four Privet Drive, the Hogwarts Express, the Burrow, Gringotts and all sets in between are all realized so well by Craig and his team, with minimal use of special effects, in a way that makes the world feel magical, very displaced from our own, but still real, still somewhere in England. It’s a tough balance to strike, but Columbus and Craig work together to shine a light on everything that there is to see, so that you get the same reaction from viewers as you did from readers, AKA: “I wish I could go to Hogwarts”.

Likewise, Columbus sought to capture the same spectacular and instantly iconic impact of the sets on the characters as well. This a very well-beloved and epic cast of characters and Columbus makes a point of giving each a strong introduction. From Hagrid to Hermione, from Snape to McGonnagall, every character in the first movie instantly pops, in a way that says, “Remember this character”, from costume design to the small minute choices of the actors. Is it a bit flamboyant? Maybe. Too much over-the-top in terms of character work? Perhaps, but this a bit of an over-the-top world in itself so it kind of works, and honestly, I couldn’t imagine doing it in any other way.

But that’s a symptom of the main flaws people bring up in regards to Columbus, which is that he made the first two movies very accessible, very viewer-friendly, but not very polished and refined. The cinematography is a bit messy and shallow, because Columbus had to cut back and forth in scenes with the young cast in order to get the best out of each. The movies are a bit long and awkwardly structured, because Columbus wanted to create very faithful adaptations of the source material. Ultimately, Columbus did the franchise more favors than he did himself as a director, and while I don’t hold that against him in any way, it does serve as an interesting takeaway regarding his approach when compared with what came later.

Alfonso Cuarón – Shaking Things Up

The third movie of the series, Prisoner of Askaban (PoA) presents probably the most noticeable and relevant change of directors in the franchise, and maybe any franchise with changing directors. Chris Columbus left and Alfonso Cuarón stepped in to direct probably the most well-made movie of the saga, and with a very different feel from the work that was done before. The first thing you notice is the color palette and camerawork. Cuarón opted for a darker scheme than Columbus in order to transmit the idea that these were no longer safe adventures for kids. The story was getting more complicated, the stakes were higher, the characters were growing up. It’s such a simple way to relay such a big idea but Cuarón makes it effortlessly. The movie is also shot more with greater care and freedom, specifically through the use of handheld shots that linger and move around, rather than cutting, allowing the viewer to analyze the behavior of the characters and the space around them in greater detail.

Cuarón also indicated to John Williams how he wanted the score to be this time around. Less exciting and bombastic, but slower, calmer, more mysterious with a hint of dread, which makes sense given the looming shadow of Sirius Black, a perceived mass murderer on the loose, hovering over the characters during the whole story.

The actors also adapt their performances to fit this style. While these characters are still quite fantastical in nature, Cuarón pushes them to deliver more nuanced, less exuberant deliveries. You can see this not only in the younger actors, who are driven to capture deeper, more emotional aspects of their characters (particularly in the case of Daniel Radcliffe), but also the adult actors match this tone perfectly. The standout scene in this respect is the confrontation in the Shrieking Shack between Snape, Sirius Black, and Remus Lupin where Alan Rickman, Gary Oldman and David Thewlis respectively milk every line of dialogue to the bone in order to sell us on the depths of the conflict between these characters. The use of long shots in such a small and deteriorated space combined with the performances makes the scene feel like a play, which is where English actors thrive the most.

The stamp that Cuarón left on this series is particularly strong. His choices in PoA are relevant to study for every lover of fantasy cinema, and they elevate the quality of the whole series of movies. Even if you don’t particularly approve of the approach taken for this installment of the series, it is undeniable that the method of movie making on display is certainly unique and distinctive.

Mike Newell – Style Over Substance

Goblet of Fire (GoF), the fourth story in the series brought with it another director shift. This time, Mike Newell took the challenge of adapting a book far longer than the ones that had come before and presented a movie that doesn’t let up from start to finish. Yes, the GoF movie is, from the very beginning, not very keen on taking its time with setting up plot elements for later reveals, and to be fair, it doesn’t really have a great amount of opportunity or time to do so.

The original book, while not being the longest of the series, is probably the one with the most going on, with a massive cast of characters beyond the ones we already knew. So, Newell really had to put the adaption hat on and see what could fit, what couldn’t and in what order and way to present the information to the audience. The result is a bit of a mixed bag. In my opinion, Newell does really, really well with the big set pieces of the movie, and not so well with small plot elements and character work.

Specifically, all three tasks of the Triwizard Tournament are very well presented, in some respects better than in the original book. The dragon fight and flight is super exciting, with amazing build-up and delivery to match, and moments of great tension and triumph. The lake dive is suspenseful and engaging, with a time limit imposed and Harry’s nobility being rewarded at the end. And the maze is by far the most frightening, with a very bleak color palette, foreshadowing the tragedy to come right after. The graveyard climax and Voldemort’s return as well as Cedric Diggory’s death are all very well executed, with performances, score and script combining to deliver on the intensity of the moments.

Unfortunately, everything else falls kind of flat. Characters are reduced to their simplest selves, bordering becoming stereotypes in some cases because Newell doesn’t devote the screen time to fleshing out what goes on deeper inside their heads. The most relevant example of this is Ron, who during the movie is either mad at Harry for entering the tournament, and when that is hastily resolved he switches to being jealous about Hermione going with Krum to the ball, which is equally bland and stereotypical, because we don’t dedicate time to explore why Ron feels the way he feels, which is more complicated than mere jealousy or angst.

Other small plot points are not given enough attention making us wonder why they were included to begin with, like the romance between Hagrid and Madame Maxime or all the suspicious eye twitching that Karkaroff does throughout the movie, or the entire character of Rita Skeeter, all of which go nowhere by the end of the movie.

Goblet of Fire presents a lesson I think, in prioritization and editing. I don’t think Newell was inherently wrong in choosing the approach he did, but if his focus was on spectacle and intensity, he should have stayed away from the more superfluous or comical aspects of the story and dedicated more time to exploring aspects of the core cast of characters which would elevate those powerful moments he excelled at.

David Yates – Competent, But Inconsistent

And finally, we arrive at the last directorial shift in the series. For the last four movies in the series, Order of the Phoenix (OotP), Half Blood Prince (HBP) and Deathly Hallows Part 1 and 2 (DH1; DH2), David Yates was selected as the director. He clearly made a good impression seeing as how he was also chosen to direct the Fantastic Beasts series. Yates’ work on the movies is a bit of a double-edged sword for me. On one hand, when his style works within the context of the story and the other elements of the movie, it works really well. But when a different tone is called for, then Yates’ inability to adapt to what the movie calls for is very noticeable.

Let’s touch on the positive aspects of Yates’ direction first, which are most apparent in his first contribution to the series, OotP. This story is not an easy adaption, but at the same time, it is probably the best adapted story in the franchise. The fifth book is the longest book, but Yates and screenwriter Michael Goldenberg did a fantastic job in trimming down what was absolutely necessary to include in a way that makes the story work on screen, something that GoF didn’t really do as well.

The tones of the story also lend themselves very well to Yates’ style. This director opts for the same dark color pallet as Cuarón, but where Cuarón contrasted that with bright lighting to compensate, Yates’ films look dark, for better and for worse. In the case of OotP, it’s for the better. You really feel the bleakness that is going inside Harry’s mind, his isolation, his misery. Hogwarts is not a particularly happy place this time around and Yates does do a lot to contribute to that sensation, not only in the colors and camera work, but in the score as well. We don’t have exciting tracks like with Columbus, or soft melodic ones like with Cuarón. All the way through the end of the series the score is somber and melancholic, with very intentional exceptions, which in this film fits really well.

Order of the Phoenix also benefits from a very strong antagonistic presence within the story in the form of Umbridge. While Voldemort’s presence is felt during the whole series, in most stories he doesn’t really appear until the very end, and in the case of this film, it’s the same thing. But Umbridge is there the whole time, being as despicable as you can imagine, as agonizingly cruel and petty as you could ever want in such a villain. I think Yates owes a lot of this movie’s success to Imelda Staunton and her performance. It is truly great work.

Finally, I do also have to commend his work on action scenes, both in this movie and the subsequent ones (with a few exceptions). Yates really figured out how to stage exciting duels between characters who just fling sticks in front of each other. The choreography is great, the effects are marvelous to look at and the camera work matches that intensity, while allowing you to see everything.

But now that I’ve praised Yates, I have to acknowledge his flaws as well. For me, his style is something that on some levels works, when called for, but in other situations is just too much and doesn’t fit. You really see that in HBP, which is a tough story to adapt because there is no ongoing conflict like you had with OotP with Umbridge. The sixth book has a lot of exposition, a lot of setting up, with honestly, not so much payoff at the end as far as action is concerned. But Yates doesn’t do himself a lot of favors here either. HBP is not a very bleak story, but Yates makes it bleak, bleaker than OotP and I don’t know why. Some scenes are so dark that it’s difficult to make out everything. This being the last story set in Hogwarts, I kind of wanted a last moment for the magic and whimsy to be felt, but there is no such sensation to be found here, no sunny days, no exciting tracks.

The structure of the film is also quite broken, with no real plot thread to follow from beginning to end, the movie feels like a bunch of small scenes with little to tie them together. At one point we’re with Slughorn, then Draco, then Harry and Hermione talking about Lavender, then a scene with Dumbledore comes out of nowhere with zero segway into it.

I think those are the biggest problems with Yates’ direction that somewhat permeate into the Fantastic Beasts series. His fondness for a particular style of filming removes a great deal of life from the world, making it only work in specific situations, and his uneven understanding of sound story structure makes it so that his movies often feel messy, with odd jumps from plot element to plot element that leave the viewer feeling like there is either too much going on or not enough.

I won’t go too deep on the Deathly Hallows movies as they possess the same strengths and weaknesses in Yates’ direction as the previous two films. As one would expect, Yates thrives in the action-packed, straightforward, emotionally satisfying Part 2, and he falters in the slow, character-driven Part 1, with the splitting of the book into two movies (a fair decision, I believe), making the structure even more difficult to handle. One can see that he is a competent director, who wants to do creative things in his movies, but as a director Yates still has to develop a grasp of different approaches to storytelling, rather than just the one he knows and is comfortable with.

Harry Potter gave the opportunity to thousands of artists to express their creativity in this particularly inventive and interesting world. I only touched on the directorial aspect of the many different lessons in movie making showcased in the series but suffice it to say that there is a lot to be said about every single facet of the craft within this franchise. It’s truly a great thing that a series made primarily with children in mind is able to introduce them to all the things that make a movie work and not work, and introduce them to many different ways to tell a single story, rather than having a single-minded view of how movies are made and what makes them good. The commitment of the entire cast and crew of these movies to realizing the story competently and rewarding viewer engagement with a product that thrives to immerse those who watch it in this world and educate on different cinematic techniques and styles is a mark of how there was true passion behind the camera and is to be commended and appreciated.